Matthew Frame is an award-winning illustrator and educator based in London. His enquiry-based practice focuses on meta-narratives within illustration and how the medium can be used to convey complex ideas and information effectively. In and exclusive interaction with Sustainabilityzero, he shares his experiences of illustrating books like Walking Is A Way Of Knowing and Speaking To An Elephant, which bring to fore the challenges faced by the Kadar tribals in south India. Matthew also touches upon his varied experiences in India, and how the country has somehow left an inedible mark on his personna and his art. Excerpts.

Can you describe your journey — evolution as an artist and an illustrator?

I studied illustration at Everton Middlesex university, graduating in 2008, in the middle of the global financial crisis.. Politics and social issues have always informed my artwork; I think my creative career has been framed in this language of austerity and debt. I did my Masters Degree at Central St. Martin’s in 2012. I was fortunate enough to meet the amazing graphic designer, Rathna Ramanathan, who has a long history of working with Tara Books. She recommended that I illustrate a book for the publishers, titled The Boy who speaks in Numbers, which is about the civil war in Sri Lanka, old through the eyes of an autistic Tamil refugee, who speaks about the world in numbers, but everyone else does in colours. It is quite a sort of surrealist narrative. It is a very sensitive portrayal of war, where there are no goodies or baddies, and it is about how children perceive events such as war. Subsequently, Tara asked me to work on another set of books about the Kadar tribe. I believe they had some issues with the Indian Forestry Commission (in terms of portrayal) due to rights and conservation issues. So, I started working on these books in a basement in London and communicating via email. And it is quite interesting with Children’s Books because there is this interplay of image and text, written simplistically. But due to my cultural background, I did not know (many things). For instance, the Kadar’s sat down to eat a plate of delicious food. And I was like, what food? What were they eating, and how could I depict it visually? It was a very collaborative experience between me, the publishers and the authors.

Then I was invited to India to be a resident artist in Chennai for six months. Coming back to England, that confidence, I think — being very far out of my comfort zone — as creative people, you kind of get stuck in a rut, sometimes. Become obsessed with having the things around you. While I was in a comfortable environment in India, it was far out of my comfort zone. It was good for me and gave me the confidence when I came back to London to get into murals, to start teaching. I taught at Portsmouth University, and now I am teaching Illustration for Graphic Design at Greenwich University.

How did illustration and drawing become your passion, and what were the influences that drove you towards art?

I was a big comic books fan when I was younger, and I pretty much spent my time in the playground in primary school drawing as many pictures as possible of Spiderman. My family also played a significant role in imbuing me with art, culture, poetry, films. Though I gravitated towards superheroes, I have always loved graphic art as a medium to communicate. Subsequently, my art evolved by looking and studying the works of people like Chris Ware or metaphors inherent in a comic book, which was also my PhD. Currently, at Greenwich University, I am looking at how Graphic art and political dialogues can interact and convey complex and contentious messages.

In this age of digitization, you are still a stickler for olden stuff – like hand-drawn designs analogue printing techniques. How would you define your style?

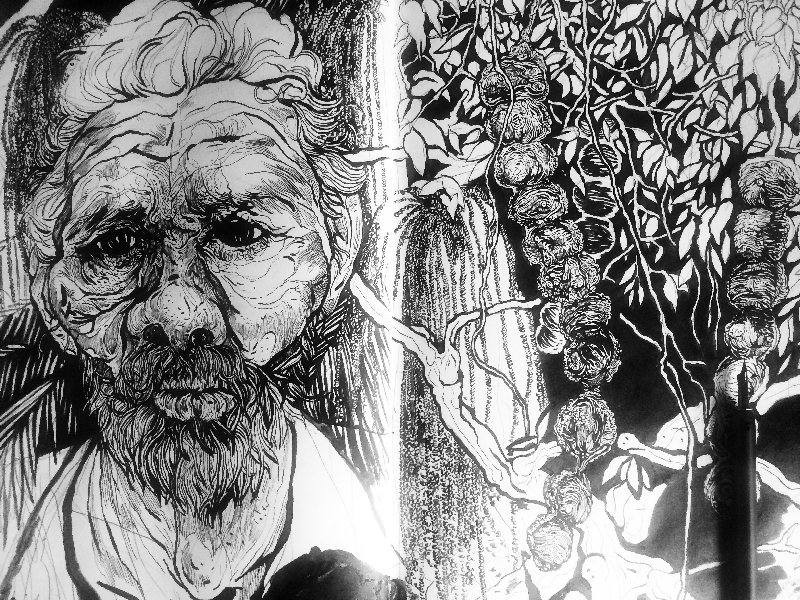

I started working the way I do because I was very much into screen printing. At the onset, I started working in black and white as I drew negatives to screen print. Artist Audbrey Beardsley, who collaborated with Oscar Wilde, significantly influenced my style. He used technology innovatively when he started drawing in the early 1800s. Illustrations, in a way, was transferred in the form of original artwork and then given to the engraver. Beardsley innovated the whole process using metal plates. He also used influences from Japan. His art was quite orientalistic in its output. As far as my style goes, I am trying to develop something timeless, something that looks from the past, present and future at the same time. And also, everything that I draw is very heavily researched. For instance, the image in Walking is a Way of Knowing and Speaking to an Elephant focuses on nature. There were no human characters in the book, even though it was about the Kadar tribe and their interaction with the deity Kadavul. The stories are about the forests and the animals. It was essential to get the research right, as research underpins my work. Thus, every mark you put on the page has to mean or represent something.

While illustrating the books for Tara, did you find the cultural elements challenging, and how did you work your way around it? Was it daunting?

It was very daunting. At the moment, I realized it was a huge responsibility when I was trying to do research. We live in this globally connected world, but if you are trying to develop a book for an old tribal community with strong oral culture and tradition but nothing in print, and you are in London, trying to figure out how to depict this. You are thinking about how to draw a tribal god, which would be in print. It was quite a challenge because there is a sort of deference and respect as a visual communicator. And it is a pretty big deal to be drawing, gods and folk tales, and how people live. One needs to have respect in that regard. So there were a few instances, wherein say, I drew a tortoise, and it was the wrong one. This was the first time, as the work I had done earlier was largely Euro-entric. The only way to work around it was through a collaborative effort, asking and interacting with the authors and the publishers, as they knew more than I did.

Climate Crisis, in this scenario, wherein we seem to be hurtling downhill, what do you think is the role of art and its purpose? I think the role of art is to show the world that things can be different than it currently is. A cultural theorist called Mark Fisher defines it as Capitalist Realism, where everything is fixed; there is no hope for change in the future. It has always been like this. It is also about accessibility. Images alongside the text make things digestible. It is also about the attention span; many times, people are very busy, art makes information more accessible.

Art is often considered to be an elitist refrain. How do you see art as a tool of change?

What I do is sort of visual communication, a graphic communicator. I see it very much linked to all the artists linked in the October Revolution. They gave up being artists and started being graphic designers and bringing the art into every day. So, art is not just for the incredibly wealthy, like John Berger outlines in the ‘Ways of Seeing’. I am very inspired by Mughal Miniatures the way they depicted everyday life. Hopefully, you can see a bit of that in my work. And more importantly, breaking this Euro-centric refrain of art, incorporating elements of the Russian avant-garde. For instance, just after World War II, the modernism art movement flourished in Britain, wherein art became a part of everyday life. The London Underground was used to inject modernist ideas into people’s lives. And graphic design and visual design became extremely important.

Graphic art is a way of liberation of that artistic expression. Is it?

Completely, when it comes to comic books, for instance. As I think that is an excellent medium for making things accessible. For instance, I recently brought a comic book on Herbert Marcuse; he is someone whose books I have read. Yet, this graphic novel helped me understand his writings much better. Similarly, access to big ideas like Critical Theory should not be solely limited to people who have access to university education. And the way into that is through graphic means.

As an artist, do you tend to get affected by the dour narratives prevalent everywhere, such as the climate crisis? How do you deal with it?

To be honest, I am essentially an optimist. I remember Theodore Adorno, the German philosopher, had famously asked how it is possible to make lyrical poetry after Auschwitz; he was talking about how art can co-exist in a world where such horrors can happen? But his plea was that you couldn’t completely give in to cynicism. I see hope, even though I am genuinely horrified what the summers will bring (in terms of climate change). What excites me most is seeing the young people, how aware, motivated, and concerned they are about the things around them, unlike when I was young.

Has India (the experiences) created some influences on your artistic style?

Of course. Before I visited India, I used to be obsessed with what I could or could not do. When I came down to India, the experience was very different. While I was not in the forests with the Kadar (tribe), it was still very much comfortable in an apartment in Chennai. After my visit, there was a change in my working style. I was not as unsure and realized that I did not need many things — I could work on my own.

And this is interesting, as I grew up in London, in Harrow, which is northwest of the city and has a vast South Asian population; we have the largest Hindu temple here outside of India. So while growing up, I had a lot of South Asian friends, so while the visit to India was very different, it was not a cultural shock. It was kind of the way I grew up. For instance, I even played Hanuman in school plays. So, I was quite at home. The most challenging thing for me in India was losing my anonymity; I stood out. There were instances of people introducing their kids to me on the trains, which was lovely, but I was a bit self-conscious.

What did you hate most about India? Was it the heat?

Not really. I managed with the heat; the mosquitoes gave me the most challenging time. When I was visiting Bengaluru, we sort of hiked up the hill, I came back, and I was completely covered with mosquito bites. None of my Indian friends were bitten by them. They were picking on the white man. And when I was in Chennai, the monsoon was terrible, and there were mosquitoes everywhere. I was covering myself in Neem oil and citronella.

And what do you love?

I loved the people. I made quite a lot of friends. I am looking forward to working on a few collaborations in India. I miss the food. The idly-dosa and learning how to use a pressure cooker were quite terrifying. I also ate quite a huge amount of Bhelpuri. And I also immensely miss the fusion food– the Indo-Chinese. I was pretty surprised how big that actually was.

Tell us something about your collaboration with Tara Books, starting with The Boy who spoke in Numbers (TBWSIN) to Speaking to an Elephant.

TBWSIN is a young adult’s book. It was my first commission for Tara. I was working in Black & White, but with that book, I had used colour. I tried to bring in a lot of South Asian street designs, like, say, sarees. I tried to bring in design elements from India and Srilanka. The book was essentially an interplay of them, displaying the horrors of war without depicting that.

When we speak of Kadar Tribe, there’s a duality of feeling — one that wants them to modernize and enjoy the amenities that come with 21st-century life. On the other hand, one feels bad for how they are being weaned away from nature — the manner in which they lived for centuries.

Indeed it is sad. Progress has a lot to do with how you demonstrate ownership over the land. Historically, if you look at the works of John Locke, who says that to own something, you need to be generating profits from it. So it does not matter that they have lived there for 100s of years. The Kadars were a nomadic tribe before the British came in, planted teak trees and made them live in the forests. And now, we have a situation where the authorities deny them the right to live their traditional lives. If I were a Kadar person, I could imagine going to the cities and escaping it all. It is unfortunate.

Let’s come now to the Speaking to the Elephant; it has a lot of animals in it. Was there any special research that was required?

I was researching the Internet for all the animals. I believe the first person Tara approached to illustrate the book was a photographer, and they managed to take some photographs in and around the forests. It did not work out for some reason. Luckily, I had those photos for reference. Then, I came across an old book that had an etching of flora and fauna of Chennai. The portraits in the book are from references, but I had to make sure they were not recognizable. I have never been to Annamalai; I would love to go there on my next trip to India.

You have received much recognition and awards for your work for the Tara Books. Have you been surprised by the response?

It is quite interesting. In my field, you get a brief, and you do it. Typically, you go through the process, and that’s it. But with these two books, I feel I have had the most prolonged response in terms of time. For instance, out of the blue, I will get an email or a post on my Instagram feed, people wanting to talk and discuss. It is an ongoing thing, and it is lovely. Like, what did I know about Indian tribal people before 2014 when I started working on these books. I am just lucky to do my job; you get to learn about new things. You get to meet interesting people, just because people ask me to do those things.

Finally, what are your plans for the future?

My practice has much moved to academia for the past few years. I am starting to work on my PhD. I am also developing some courses in Greenwich, part of the graphic design course, illustration and art-based. I recently illustrated a book called the Bright Labyrinth with one of my lecturers from Central St. Martins, based on a set of 10 lectures that he gave and sort of blew my mind. And now, I have done some drawings, which he is writing about. This is quite nice, an interesting inversion, as the illustration is not merely decorative addition to someone else’s text. It is an art form that stands on its own. Hopefully, we will publish that soon. I also started a publishing house with a graphic designer friend of mine.

Message to young graphic artists?

It may sound clichéd, but finding your voice is very important. You need to decide what is important to you, don’t follow trends, don’t do whatever others are doing, don’t draw work just for Instagram.

-- Shashwat DC

Recent Comments