We humans are truly a rare species. We are fighting a war that we ourselves have triggered. For years we have unscrupulously destroyed the environment; depleting our resources and are pushing animals towards extinction. Global warming is the consequence of man’s greed and avarice; it is nature’s answer to the dastardly acts of man. Sustainable development is the new buzz word created to curb global warming.

Energy is a critical requisite for economic growth, especially in a developing country like India. It is one of the most important sources of any industrial activity. However, its availability is not infinite. The textile industry is known to be one of the most polluting and energy intensive industries. It comprises a large number of plants, which all together consume a significant amount of energy.

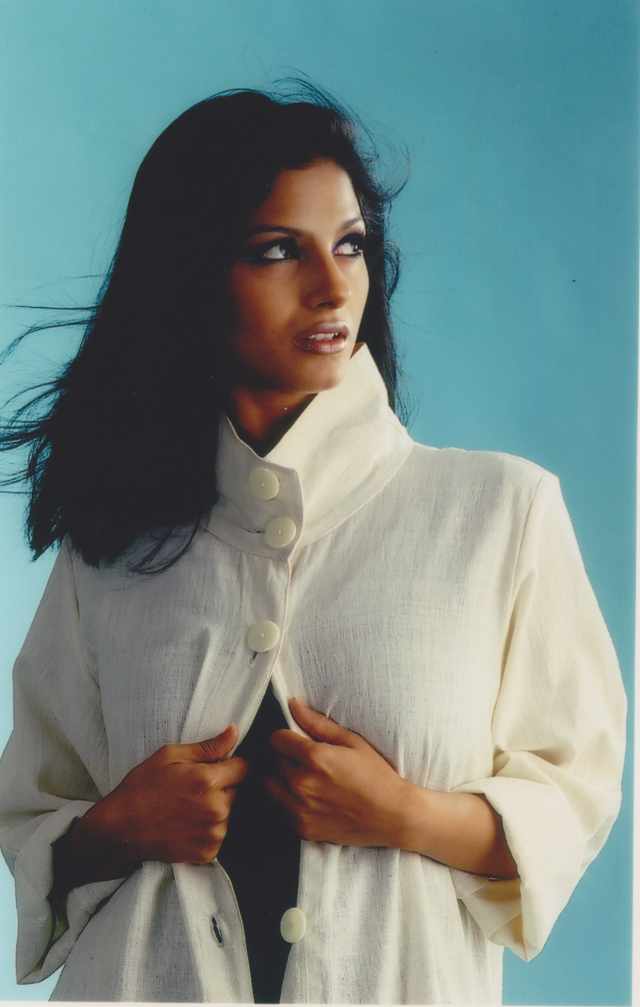

Countries around the world are looking for ways and means to reduce the carbon footprint within textile industries and are spending heavily towards less energy intensive technology. India too is following this trend, and many of us have overlooked low energy alternative like khadi, that is eco-friendly and handmade.

Overview

Unlike other fabrics, khadi has stood as a testament of India’s past and is proof that “old is truly gold”. Despite the competition from other fabrics, khadi has survived. There is often an erroneous assumption that links khadi with other handloom products. What distinguishes khadi from handloom is that khadi is hand-spun with the help of a charkha whereas handloom yarn on the other hand, is processed in the mill. This is what makes khadi so unique and diverse as it keeps the wearer warm in winter and cool in summer.

The production of khadi is an extremely judicious process, taking the environment into consideration, right from the spinning to the weaving. Mahatma Gandhi’s premise for promoting khadi was to increase employment in the non-farm sector. However, according to reports, between 1997 and 2000, “The sale of khadi plunged by more than Rs 100 crore to Rs 631.79 crore. If it employed 14 lakh people in 1997, it employs only 12 lakh today.”

The khadi village industries village,

which is a government body, was set-up primarily to promote this initiative.

However, the huge subsidies have done nothing to promote the garment. The

failure on the part of government agencies to promote the material has led a

number of designers to revive the once popular material.

Low Carbon Footprint

All textile processes have an impact on the environment. The industry uses large amounts of natural resources such as water, while many operations use chemical sand solvents. All companies use energy, produce solid, discharge effluent and emit dust, and toxic gases into the atmosphere.

In modern times, the clothes we wear like everything else we use—consume power or electricity and also energy—from the making of the thread or yarn, the cloth, packaging, marketing to the merchandising until it reaches the consumer. That would mean, use of gas and coal for making electricity to run the machines, making plastic for packaging and use of petrol for transportation, which in turn means more coal mining, oil drilling, thermal power plants or nuclear power.

Assistant Professor Sarita Sharma of International College For Girls, Jaipur, in her paper titled, ‘Energy Management In The Textile Industry’, “In India, the textile industry is one of the major energy consuming industries and retains a record of the lowest efficiency in energy utilization. About 23 percent energy is consumed in weaving, 34 percent in spinning, 38 percent in chemical processing and another five percent for miscellaneous purposes. In general, energy in the textile industry is mostly used in the form of: electricity, as a common power source for machinery, cooling & temperature control systems, lighting, equipment etc; oil as fuel for boilers, which generate steam, liquefied petroleum gas, coal.” The need of energy management has assumed paramount importance due to the rapid growth of process industries causing substantial energy consumptions in textile operations.

With global warming becoming a serious concern, energy conservation has become crucial. Today in India, the words ‘green’ and ‘eco-friendly’ have become quite dominant in a world plagued by pollution and GHGs. India is constantly looking for ‘green solutions’, which can help mitigate global warming. The irony of it all is that India has the most sustainable and eco-friendly product—khadi. As khadiis made from cotton, silk and wool and is spun and woven manually ie without any electrical support, it becomes the only activity that is not utilising fossil fuel. If dyed with natural dye it becomes a green fabric.

The greatest advantage of khadi is that it carries the lowest carbon footprint. Production of one metre khadi fabric consumes just three litres water against 55 litres consumed in a conventional textile mill. Many question the ecological impact of khadi; citing reasons such as transportation and packaging as extremely carbon intensive however, the hand woven fabric has a much smaller carbon footprint, 28 percent less, even when shipping is factored into the equation. The making of khadi is eco-friendly since it does not rely on electric units and the manufacturing processes do not generate any toxic waste products. In fact, in some states like Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, organic khadi is produced by avoiding all chemicals involved in the farming of cotton and during weaving and dyeing of fabric.

Energy Efficiency

In a paper titled, ‘Khadi: Effective Energy Conservation Production Model’ published by Nimisha Shukla and Sudarshan Iyengar, “Out of one kilo of cotton, considering 10 percent wastage, one hand of 1,000 yarns can be produced on the ambar charkha with two spindles with human energy, which would take 50 minutes. On the other hand, to weave one metre of khadi, six to seven hands are required that would take 1.33 human hours. In all, it takes 2.25 human hours to produce one metre of khadi. If we apply human work output in agriculture—that is equal to 0.1 HP (Horse Power) or 0.074 kWh—to khadiproduction we would get 0.225 HP or 0.17 kWh energy-equivalent for producing one metre of khadi. Hence, assuming that a labour uses only one/one hundredth of power, the estimate would give us 11.1 million metre of charkha yarn production from population employed only in agriculture. As against khadi, to produce one metre mill cloth, 0.45 to 0.55 kWh electrical energy is required. This means that khadiis approximately 3.24 times energy efficient than mill cloth.”

Presently the production of cotton slivers from ambar charkha uses electricity. Yarn production from the ambar charkha, therefore, cannot be said to be entirely energy conserving. In 2007, the Khadi and Village Industry Commission introduced the e-charkha, which enables a spinner, to spin yarn and also generate enough power to light up his/her home and listen to a transistor.

Decline Of Khadi

Khadi, which Jawaharlal Nehru called the “livery of our freedom”, is in tatters today. The material that symbolized self-reliance and emancipation during the freedom struggle has lost its sheen over the years. And there are several reasons for the same. Post-1947, India opted for state led large scale industrialization. With many Indian industrialists setting up huge textile mills, the mass production of fine cloth led to the availability of cloth at lower prices. People began to buy machine made textiles and thus khadi began losing out to the mill fabric. Its importance diminished and it was relegated to the background by the more svelte and “fashionable” garments such as silk, denim, leather and fur. The competition from mill-made textiles and imported fabrics are one of the reasons for the declining sales.

Also, the saleability of any textile depends on its USP and performance. For many years, the promotion of khadi had been on emotional and political grounds while its quality and variety had been ignored completely. And, unlike other fabrics, khadi has very little to offer in terms of fabric performance or versatility, which is why consumers and designers prefer to patronize other fabrics. Khadi requires maintenance. It looks attractive when starched and kept in a showroom, but it does not remain the same after washing. Even finer counts and blends of khadi cannot withstand many washes and is thus not conducive for day-to-day purposes. This is a significant though hotly debated issue. A typical middle class Indian would opt for synthetic materials over khadi since the latter requires careful laundering and looking after, believe designers.

Another factor that is threating the existence of khadi is the cost. Most handloom products are expensive because the manufacturing process is extremely laborious and physically demanding. Farmers pick out cotton from fields. These cotton balls are very coarse in nature and the fibres have to be separated from the seeds by hand using a sharp comb-like object. A process called ‘carding’ removes the final traces of waste from the cotton to produce what are called ‘slivers’. These are then spun into a yarn on a spinning wheel, or a charkha, which thins out the slivers and twists them at the same time, thereby strengthening them. It’s a long and completely manual process. Handmade fabrics are going to become more and more expensive because their production capability is low. Regular fabrics are being produced at the drop of a hat through technology; a fabric that takes so much manmade labour is obviously going to be expensive. For designers like Wendell Rodricks, “Wearing khadi is not just about being fashionable and trendy; it is about having a conscience and living that belief. As long as people are conscious about the environment, khadi will always have a market and price won’t be a factor.”

Middleman Blues

Considering the amount of effort involved in the manufacturing of khadi, if weavers spend hours spinning and weaving and receive little returns, they will eventually migrate to other occupations. To add to this, middlemen exploit weavers by pocketing profits earned on sale of khadi cloth. The middlemen quote a much higher price than its actual cost and pay the weavers inadequately.

The art of weaving is a trade, which is passed down from generation-to-generation. If weavers are not receiving enough remuneration, the next generation would discontinue with the legacy, and pursue other professions. The declining workforce strength in the khadi industry is making the productions of khadi seem very challenging. And without skilled weavers, the future of khadi may be on the decline.

Valuing Our Legacy

Indians today, live in a westernized society that takes pride in everything that is foreign. We are constantly looking towards the west for inspiration in terms of designs, innovative products, and are always comparing ourselves with the west. India has a rich culture and heritage which unfortunately is under-valued by people who take pride in portraying a foreign culture. Indian garments that are exceptionally rich and beautiful; replete with intricate embroideries and designs—defining the myriad cultures of different states are often not acknowledged by Indian designers who want to find favour with the rest of the world. The necessity of bringing khadi to the fore is essential not only because it is sustainable, but also because it is inherent to our history and Indian culture.

Designers’ Take

The government

needs to take cognizance of the soaring prices. However, fashion designer Rahul

Mishra feels differently. “The softest cotton to ever be produced is khadi. The

reason being, it is hand spun and hand woven. The soft texture of khadi cannot

be produced in a machine. So khadi is sheer luxury and that’s what consumers

need to understand; it is 100 percent couture. Take for eg in China, one

machine is producing 10,000 metre of regular cloth a day, and on the other hand,

when someone is using khadi yarn, we are producing the textile is just three

metre a day.” So should the price of khadi be reduced? “No!” he replies vehemently.

“If people are willing to spend money on luxury items why should they have a

problem with khadi?”

Sunaina Suneja, Fashion Designer, is of the same opinion. “For something that is handmade, I personally do not think it is that expensive considering how much effort it takes to spin the yarn. I don’t think it’s that expensive.”

Vision Of A Sustainable Industry

Khadi is sustainable not only because it doesn’t take much of a toll on the environment, but also because it provides employment. The logic of shifting to khadi may be convincing but its adoption has not been easy due to the reasons cited earlier.

According to author, Nimisha Shukla, “Sustainable consumption is related to two aspects. The aspect of “needs”, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which, overriding priority should be given, and the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs.” Economically backward populations in vulnerable regions are going to be hit by the swindling of the natural resources by the large industries. Gandhi’s vision for decentralised production system was because of this reason. The more decentralised production and distribution system better is the control people will have on their destiny. It is clear that because khadi is hand spun, it will not be able to meet the total clothing requirement of the world’s population, but even if one fourth of the demand is met through this low and clean energy technology of khadi, India’s contribution to slow down the global warming will be substantial.

Recent Comments