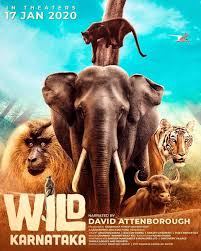

A visual spectacle is how you would describe Wild Karnataka. Watching it unfold is like a beautiful canvas, full of flora and fauna; soothes your nerves and makes you a little wistful. For quite some time into the film, I was finding it hard to believe that such pristine landscapes do still exist. My brain accustomed to the majestic recreations of CGI was finding it hard to believe the claim that all that green that we were watching was actually so, and now recreated over a green canvas in chroma.

The film runs just under an hour, is breathtakingly beautiful. It has been delicately shot and put together with much tenderness and care. According to the director Amoghvarsha JS, the film has been in the making for a good four years. Three years to shoot the wild, and one year putting it together. The hard work resulted in footage of 400 hours that was culled into the short snappy docu-film. The high-point of the film is the voice of Sir David Attenborough, who takes us on a journey of a year through Karnataka’s wildscape. There’s a palpable excitement in Amoghvarsha’s voice when he talks of how they convinced Sir David to lend his voice to the project. One of the biggest challenges faced by the team was to have Sir David to pronounce the local words. This called for some creative thinking, like spelling Karnataka as Kur-nataka. Having grown up with the assured voice of Sir David, the film Wild Karnataka seems like one of those international documentaries that keep airing on Discovery and NG.

Yet, the best thing about the movie is that it is an out and out Indian effort, even though it was made in collaboration with a British Studio. All the film-makers are homegrown wildlife photographers, who have spent days and months trying to get the perfect sequence. Unlike the foreign makers that do not have to worry about finances, this film was in a very cost-conscious manner. The great Indian jugaad that was able to send a spacecraft to Mars at a fraction of the cost of NASA is at display here. Much of the aerial sequences are not shot on Helicam but everyday drones. Amoghvarsha talked about how to get a steady shot from a jeep; they had taped a common drone on the bonnet instead of going for a hi-fi camera system that would have cost a bomb.

Coming back to the central characters of the film. The film is full of tales of how Davids take on the Goliath. For instance, there is a little footage of how a family of otters takes on a Tiger that jumps into their river. While on land, the tiger is high-and-mighty, the easy-going otters are the masters in the aqua medium and make it evident to the striped super-predator. In another sequence, you have a Sambhar deer mom protecting her young one from a pack of wild dogs or Dhole. The little one is scared and rivetted in the pond, while the mom takes on the dogs, attacking them till they back off.

The usual suspects are there, the elephants, tigers, leopards, jaguars, and others. But what is unusual is to get a glimpse of the dragon, or the flying lizards — Draco. These creatures glide long distances almost 100 feet from one tree to another. And there’s a romantic sequence of a love-struck Draco in the film.

The film ends with a sequence of the majestic Jog Waterfalls. The sheer drop of the water creates this pristine curtain of white mist that makes you sigh in wonder. There could be no better “call of the wild” than this one if this was the best sequence for me. The best shot was of a solitary elephant from the top trudging along at Kabini, touted as Elephant’s Shangri-la. While the actual elephant is camouflaged in the green-brown hues of the land, it is given away by the majestic shadow it casts on the earth. The shot is fantastic, the once-in-a-lifetime kind of capture. I can still close my eyes and picture that shadow floating on the ground.

Wild Karnataka is fantastic, but there were a few niggles too. There were a tad bit more sequences that were included. I would have preferred more in-depth coverage of some species rather than a limited coverage of a lot many. For instance, the peacock sequence could have been done away with, even though Sir David hailed it as excellent. Or the frog-dancing one could have been edited out, as it did not add to the narrative. I would have loved to see a time-lapse of all the Cobra egg hatching or even a lengthier pursuit of our Romeo Draco. But then these are individual preferences, and each could have his or her own.

The film kinds of lacks in “action” as we are accustomed to in wildlife documentary films. There is no edge of the seat kind of battle that makes us squirm or sympathetic. Typically, such films rouse your emotions, a hunt by a predator is usually the action part. Indeed there’s one sequence of a leopard that makes a dash and climbs a tree while chasing a langur, but then as primate escapes, the sequence ends in just a few seconds with the feline dropping to the ground.

Secondly, the emphasis on Karnataka seems a little odd. I mean, Karnataka is a part of India. And the wildlife and the ecological beauty is not a property of the state but the nation. Just like the Lions of Gir do not belong to Gujarat alone, but are a national heritage. Also, the film frequently references the Western Ghats as the ecological wonder. But the Western Ghats are not exclusive to Karnataka but cut across Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, and Kerala. The Western Ghats belong to the nation and not a particular state.

Similarly, flora and fauna of Karnataka are quintessentially Indian. When I raised the same issue with Amoghvarsha at the screening, he explained it by saying that the genesis of the project started with the thought of chronicling something local. “We started small, but then it just kept growing bigger.”

Also, being a father of young kids, I could not help but wish that if this film could be dubbed in Indian languages, say in Hindi by Amitabh Bachchan and in Malayalam by Mammoty, the reach could increase manifold. The film has been dubbed in Kannada, I believe, and is being taken to schools in Karnataka. I wish there are so many more local copies of this film.

A special shout out to the music composer Ricky Kej. He has done a brilliant job, of animating the beautiful sequences with background score. The use of Indian classical music, especially the flute adds a mellifluous touch to the movie. The soundtrack makes the film more vivid and stays with you, even after those 50-odd minutes of run time.

In the end, Wild Karnataka is a fantastic watch worthy of being viewed on the big-screen (read cinema) with all the jing-bang of Dolby sound and so on. The film could be the beginning of a new genre in India. There could now be many more natural-history film-makers that might emerge from India. Amoghvarsha was a software engineer at Amazon before he decided to pursue his passion. I am sure there are many more just waiting to hatch given the right conditions, like those little cobras in the film. Don’t miss the movie is all that can be said.

Recent Comments