— Nick Barter

Environmental and social degradation precipitated a call for sustainable development and in 1987 the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development report ‘Our Common Future’ (1987), defined sustainable development as “development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.

Currently, sustainable development is accepted as an idea of general usefulness that is  important for organizations and leaders to embrace. In particular, “corporate strategists” have been identified as key actors to enable sustainable outcomes, individuals who in turn should have a “special focus on climate change as a sustainable development challenge”. In this regard, although not equivalent to, it is evident that climate change is considered as a component part of the sustainable development challenge.

important for organizations and leaders to embrace. In particular, “corporate strategists” have been identified as key actors to enable sustainable outcomes, individuals who in turn should have a “special focus on climate change as a sustainable development challenge”. In this regard, although not equivalent to, it is evident that climate change is considered as a component part of the sustainable development challenge.

While climate change may be considered a component part, it is worthwhile considering the underlying narrative of sustainable development. The definition highlighted above puts humans as the priority and in this regard, although self-evident, it is worth reiterating that sustainable development is a narrative written by humans for humans. Further it is one that considers our well-being and continued survival. In turn the concept of sustainable development does not consider the environment or for example the climate as some abstract separate conceptual space. Rather, Our Common Future, the 1987 United Nations publication highlights that to consider the environment as something separate to us is naive. In this regard sustainable development requires a more systemic understanding of humans and their interactions with all that surrounds them, it is arguing for a move away from considerations of separateness to those that recognise the interconnections, with humans as key actors.

This conceptualisation of humans being the primary actors shaping their surroundings (the world around them) is captured in Crutzen’s (2006) claim that we now live in a new epoch; the anthropocene. This epoch, where humans are considered the primary shapers of everything around them also brings forward a new era of responsibility for our continual prosperity in so much as we have to take responsibility.

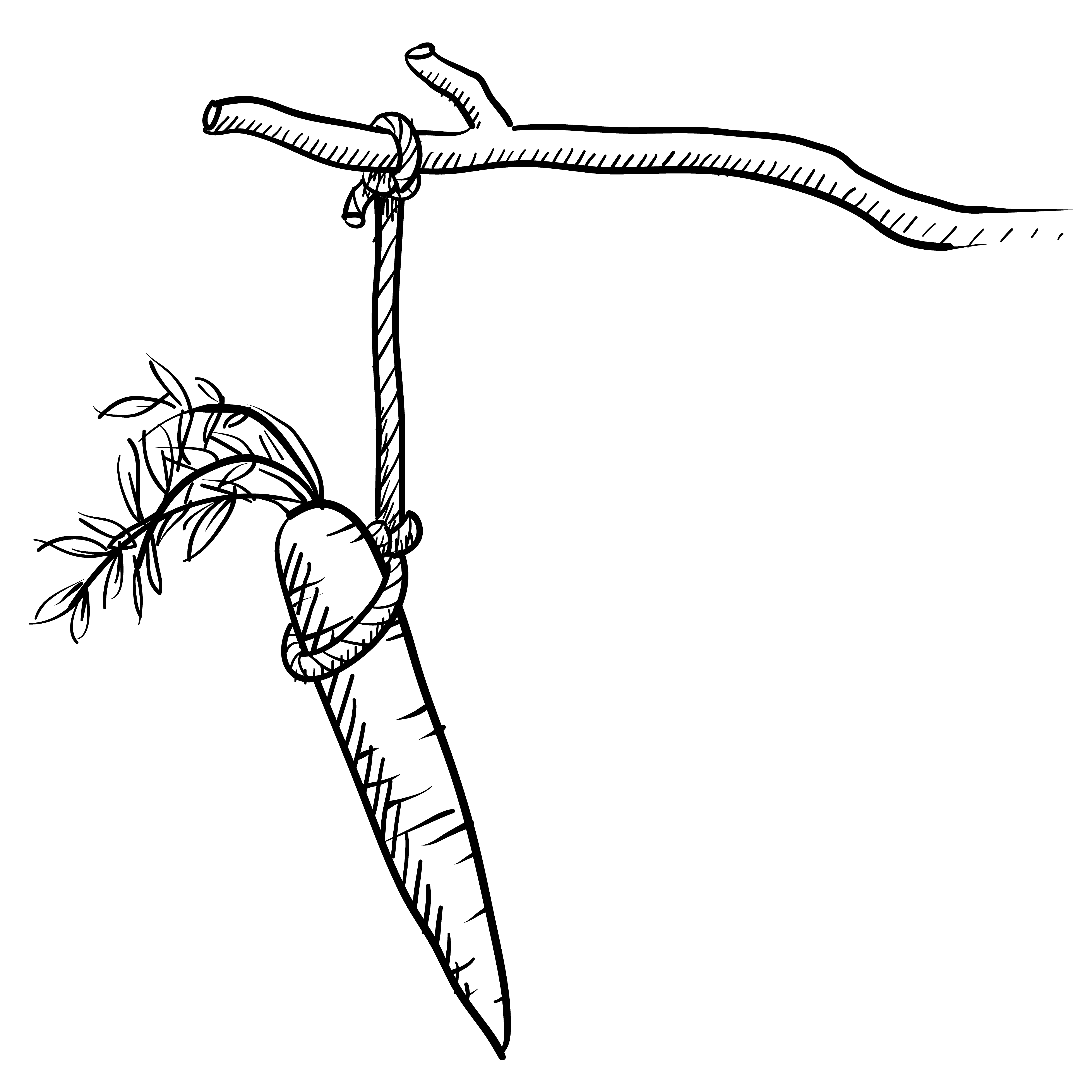

While it can be accepted, given the power of corporations that the weight of responsibility for continued prosperity falls to corporate strategists; the challenge behind this is what drives corporations, what incentives or penalties can be used to drive their behaviour. Turning to the carrot and stick metaphor, within the context of its use regarding the amelioration of climate change by organizations, the metaphor indicates that organizations will change their behaviors through monetary incentives (subsidies – carrot, taxes – stick). Thus the assumption is that monetary gains and losses are all that matters. The implication being that no other form of subsidy or tax (perhaps non monetary) will change organizational behavior. Further this implies that organizations exist in an isolated bubble, as if economic decisions have no impact on society or the environment; as if the economy, society and the environment are separate conceptual spaces with no or minimal overlaps. While historically such a conceptualization has organizational theories, it is worth noting that this form of knowledge construct is an antithesis to our lived reality. The decisions of organizations do impact society and our surroundings. For example an economic decision not to ameliorate polluting outputs can impact air we breathe, the water we drink and perhaps the fish we catch or the forests we walk in. Similarly a reduction in the wages of employees

While it can be accepted, given the power of corporations that the weight of responsibility for continued prosperity falls to corporate strategists; the challenge behind this is what drives corporations, what incentives or penalties can be used to drive their behaviour. Turning to the carrot and stick metaphor, within the context of its use regarding the amelioration of climate change by organizations, the metaphor indicates that organizations will change their behaviors through monetary incentives (subsidies – carrot, taxes – stick). Thus the assumption is that monetary gains and losses are all that matters. The implication being that no other form of subsidy or tax (perhaps non monetary) will change organizational behavior. Further this implies that organizations exist in an isolated bubble, as if economic decisions have no impact on society or the environment; as if the economy, society and the environment are separate conceptual spaces with no or minimal overlaps. While historically such a conceptualization has organizational theories, it is worth noting that this form of knowledge construct is an antithesis to our lived reality. The decisions of organizations do impact society and our surroundings. For example an economic decision not to ameliorate polluting outputs can impact air we breathe, the water we drink and perhaps the fish we catch or the forests we walk in. Similarly a reduction in the wages of employees  impacts the locale as well as the ability of the organization to sell its products and services. The cutting of wages means that the money available to people to buy those products and services is reduced, as money is moved from those who would consume to those who invest; investors by definition are a smaller number. Thus through a monetary lens many decisions for an organization can be self-defeating. Likewise with regard to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions the non-amelioration of them will result in disasters that will impact all (investors and consumers alike): not just individuals’ abilities to earn money, but also where they live and ultimately whether they live at all (a necessary precondition for economic exchange) if some of the predictions regarding weather and sea-level patterns are accepted (IPCC, 2014).

impacts the locale as well as the ability of the organization to sell its products and services. The cutting of wages means that the money available to people to buy those products and services is reduced, as money is moved from those who would consume to those who invest; investors by definition are a smaller number. Thus through a monetary lens many decisions for an organization can be self-defeating. Likewise with regard to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions the non-amelioration of them will result in disasters that will impact all (investors and consumers alike): not just individuals’ abilities to earn money, but also where they live and ultimately whether they live at all (a necessary precondition for economic exchange) if some of the predictions regarding weather and sea-level patterns are accepted (IPCC, 2014).

In this regard, the carrot and stick metaphor, if focused on monetary incentives alone is limited as organizations have a plethora of impacts and to limit or reinforce a focus to monetary outcomes through taxes and or subsidies (carrot and stick) is myopic. Not least because monetary outcomes are a function of peoples spending habits, they cannot be abstracted from them and as such the economy is nested with in society, the economy is not a separate conceptual space.

Consequently while economic outcomes matter, they are not all and the responsibility of organizations extends beyond money especially in a world of limited government abilities relative to the power of corporations and a requirement for sustainable outcomes. As such a carrot and stick focused only on the metrics of money is limited in its ability to tackle climate change. In turn given the conceptual understanding that the economy is nested, not free floating, money should not be the only weapon in the armoury to enable organisations to tackle climate change. A point made especially clear when we consider human motivation and how we are not solely motivated by money.

Although a relatively old paper, that humans are not motivated solely by money is a point made clear by McGregor’s 1957 discussion of the human side of enterprise. In this paper he argues that the carrot and stick theory of motivation works relatively well if an individual is  struggling for subsistence. However once subsistence needs are satisfied the meeting of psychological needs (feelings of purpose and wellbeing) motivates people not the meeting of their physiological needs as provided for through money. Further in the absence of meeting higher needs individuals’ use money to ameliorate the absence of higher needs being met by buying goods and services that provide some limited satisfaction (McGregor, 1957).

struggling for subsistence. However once subsistence needs are satisfied the meeting of psychological needs (feelings of purpose and wellbeing) motivates people not the meeting of their physiological needs as provided for through money. Further in the absence of meeting higher needs individuals’ use money to ameliorate the absence of higher needs being met by buying goods and services that provide some limited satisfaction (McGregor, 1957).

By extension, the decision makers in organisations are perhaps on the surface driven by monetary gains but that will only be because monetary gains or losses for the organisation facilitates their moves in an organisation structure perhaps to a new or higher leadership role that actually meets their psychological needs. Consequently, even though monetary gains or losses (a carrot and stick) are applied to an organisation, it is likely to be ultimately a limited and sclerotic instrument. Thus the focus should be on the enablement of an organisation and in turn the decision makers to realise a higher order purpose. For example perhaps incentivising organisations not just through taxes and subsidies but through policy that allows the organisation to demonstrate purpose. This said it will require an imaginative and brave government to pursue such a path and in that regard, it is likely that the simplistic of taxes and subsidies will be followed.

The Carrot and Stick – Wider Evidence

In 2001, Dickinson conducted a study on the carrot vs the stick in work team motivation. In this study he found that teams’ contributions to goals are highest when teams are allowed to penalise some and reward others as they see fit relative to the overall performance and abilities of each team member. Thus carrot and stick incentives work but only when account is taken for relative ability. Similarly, Sutter et al’s (2010) study of institutional choice in social dilemma situations found that outcomes are most efficient when groups set the rules for themselves albeit their study also found that rewards (carrots) are the preferred choice of groups.

Outside of these studies, Kverndokk et al’s (2004) study on carrot and stick policies relative to climate change found that taxes are generally better unless subsidies will create research spill over effects. However as spill over effects are difficult to predict or be sure of, Kverndokk et al (2004) favour taxes because subsidies may prop up an existing technology that is sub-optimal, hindering the development of new and better technologies. Further subsidies may encourage outside participants too enter the subsidy framework to receive the benefit and thus compound the hindering of progress. In sum, taxes are perhaps a more neutral and efficient means of creating change. A line of reasoning reinforced by Galle (2012) who argues that with regard to policies “sticks are usually superior to carrots” and that carrots only tend to contribute to polluters’ incentives “to raise the political stakes, either by cranking out more negative externalities or withholding benefits”.

Outside of these studies, Kverndokk et al’s (2004) study on carrot and stick policies relative to climate change found that taxes are generally better unless subsidies will create research spill over effects. However as spill over effects are difficult to predict or be sure of, Kverndokk et al (2004) favour taxes because subsidies may prop up an existing technology that is sub-optimal, hindering the development of new and better technologies. Further subsidies may encourage outside participants too enter the subsidy framework to receive the benefit and thus compound the hindering of progress. In sum, taxes are perhaps a more neutral and efficient means of creating change. A line of reasoning reinforced by Galle (2012) who argues that with regard to policies “sticks are usually superior to carrots” and that carrots only tend to contribute to polluters’ incentives “to raise the political stakes, either by cranking out more negative externalities or withholding benefits”.

In the end, moving through the myriad debates on climate change, it does emerge that to ameliorate climate change taxes (the stick) are likely to be the most effective tactic because they are the most neutral instrument and also ultimately transfer wealth to society as opposed to the opposite with subsidies. And while that is so, one needs to bear in mind that more fundamental concern regarding climate change being a systemic issue and more weapons in the armoury should be used to alter organisational behaviour than just monetary ones. However to move beyond a monetary carrot and stick will require a brave government and a more systemic view of how government can use its powers to craft a sustainable society that is employed and has the money and desire to spend on organisations products and services and thus ensure their prosperity. Especially because it is oft forgotten that the organisations have no right to exist in their present form and are unlikely to with the systemic changes that will be unleashed with climate change and thus all should be a little more adventurous and systemic in their points of leverage for change.

—–

Associate Professor Nick Barter is the Director of Griffith’s MBA program, deputy director of the Asia-Pacific Centre for Sustainable Enterprise, a senior lecturer at Griffith Business School in the Department of International Business and Asian Studies, an International Associate of the Centre for Social and Environmental Accounting Research and the UN PRME co-ordinator for the Australia/New Zealand region. His research explores sustainability and business strategy with a particular focus on developing strategy so that it is fit for purpose in the 21st century and can help realise a new ‘future normal’. He can be reached on n.barter@griffith.edu.au

Associate Professor Nick Barter is the Director of Griffith’s MBA program, deputy director of the Asia-Pacific Centre for Sustainable Enterprise, a senior lecturer at Griffith Business School in the Department of International Business and Asian Studies, an International Associate of the Centre for Social and Environmental Accounting Research and the UN PRME co-ordinator for the Australia/New Zealand region. His research explores sustainability and business strategy with a particular focus on developing strategy so that it is fit for purpose in the 21st century and can help realise a new ‘future normal’. He can be reached on n.barter@griffith.edu.au

Recent Comments